by Christina | May 7, 2025 | 2025

Your best copy might sound like AI to clients. See why creative value is under pressure and what it means for agencies.

AI is changing how clients view creative work. Even the best human efforts are starting to be questioned — not for quality, but for authenticity. I recently saw this firsthand.

The feedback I was not expecting

Below is recent feedback from a client on some content we created.

“I do have a piece of feedback for them. I’m not sure which AI writing tool they’re using to create these, but they may want to take a second pass… a lot of these pieces of copy are clearly first pass AI generations…”

The problem is that our copywriter didn’t use AI and would be offended by the feedback. He’s an award-winning creative with a big agency background. As you might expect, he’s vehemently opposed to using generative AI.

Where is the feedback coming from? It’s from a company whose marketing department strongly embraces generative AI for content creation. I guess they assume their agency is using it as well.

That will be a significant issue if you are on the agency side. Perhaps it already is, and I’m just now experiencing it. Our copywriter is very talented and has a lot of great experience. As a result, he is not inexpensive.

He warrants the rate he receives, now threatened by clients who will discount the value, assuming a tool is responsible for his output.

As more clients adopt generative AI tools for marketing, questions will arise regarding the outputs and cost of agency services, particularly creative agencies.

In this example, it’s content. However, the same scenario could apply to any creative service: creative concepting, AI image generation, media planning, AI audience segmentation, etc. AI is everywhere.

The real problem behind the perception

The reality of AI tools is that they are handy and efficient. As a result, we face the challenge of protecting the craftsmanship of our creative resources while leveraging the tools’ value.

I’ve always believed that good copy or content is an art. But what happens if no one appreciates the art? What will be its value?

Many creatives use AI tools for ideation, content refinement, editing, etc. However, to date, I’ve not seen any evidence that AI-generated or modified outputs perform any better than what humans have created in the past.

Dig deeper: What AI means for the future of agency-brand partnerships

AI vs. human-generated content

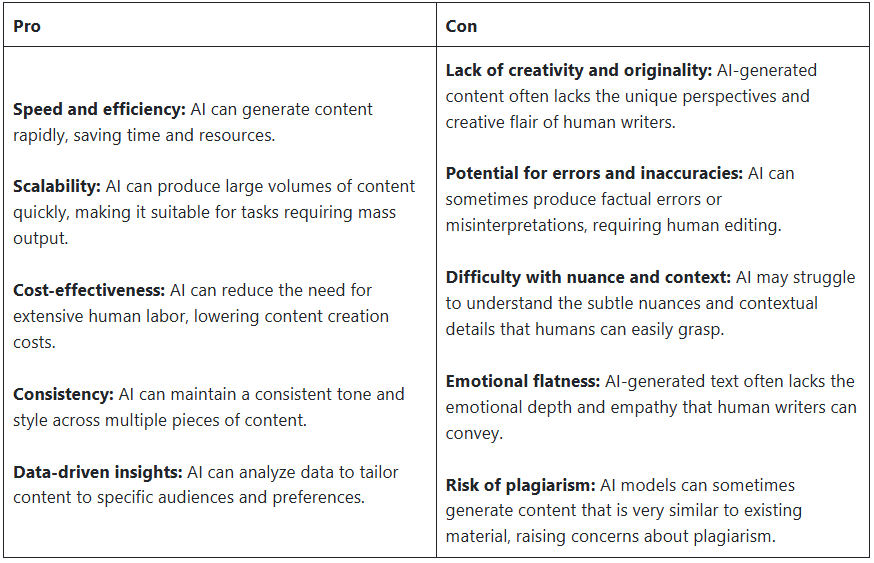

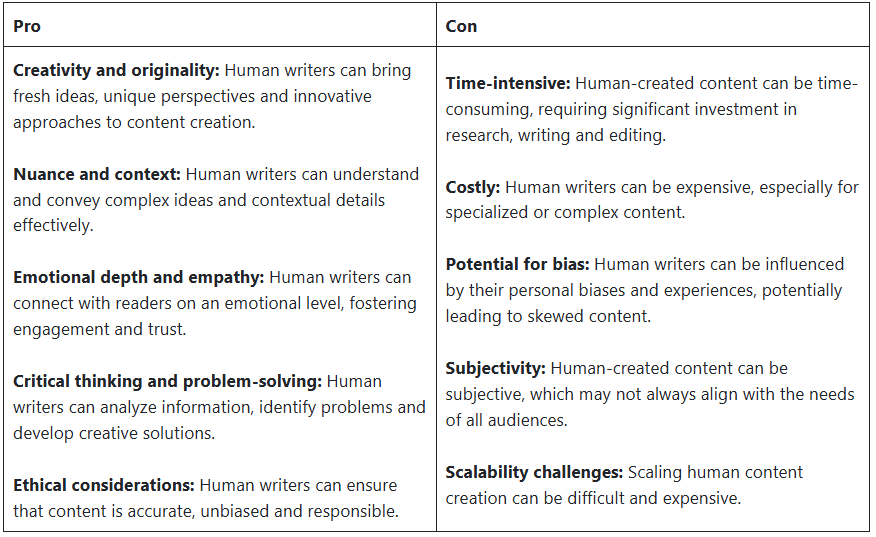

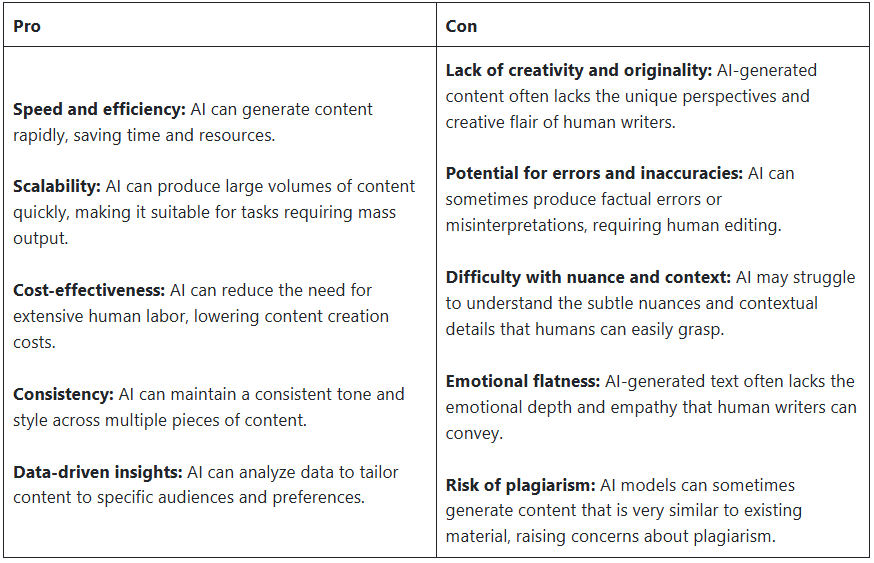

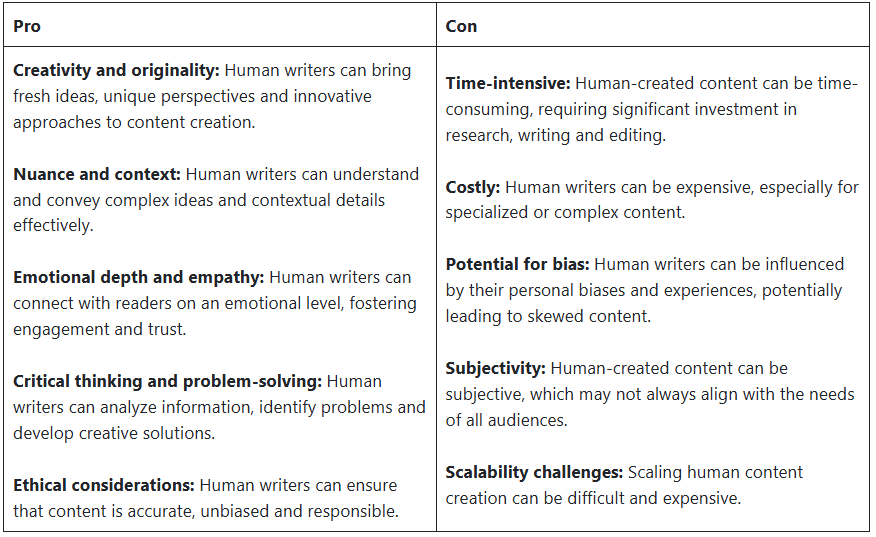

Maybe it’s not a choice of “either-or,” but knowing the advantages and disadvantages of each approach (see below) and when to use them situationally to our advantage.

AI-generated content

Human-generated content

Dig deeper: https://martech.org/riding-the-ai-tsunami-harnessing-creativity-and-efficiency-in-the-digital-age/

The blended future of creativity

After pulling this together, I realized where the client feedback came from in our latest content round. Over the last few months, we have been hand-crafting emails for announcements, follow-up emails to events and other marketing outreach activities.

This most recent round, and what generated the feedback, was a change in our approach. We profiled the personalities of the target audience and found that the most dominant personality type was one that prefers concise, to-the-point, no-nonsense content.

We removed the “emotional depth and empathy” mentioned as a strength of human-generated content. As a result, the content had an “emotional flatness,” making it sound like a machine wrote it. The blending of machine and man is not going away. The only real question is, will it improve our results?

Dig deeper: The AI-powered marketer’s roadmap to the future of content

by Christina | Mar 13, 2025 | 2025, Business Trends

5 Ways to Protect Against an AI Bot Attack

Businessman and former Presidential candidate Andrew Yang once said, “Automation is no longer just a problem for those working in manufacturing. Physical labor was replaced by robots; mental labor is going to be replaced by AI and software.”

AI bots are starting to deliver on that promise in the market research arena, to the detriment of research practitioners and their clients. Recently, we deployed an online survey for a client, dangling a financial incentive for completing the twenty minute questionnaire. As soon as the link hit social media with the financial incentive the AI bot sharks smelled blood in the water.

Within a few hours we had over 400 completed forms, and over 1,500 (!) within a day. And their completion rate was much higher than among our real human survey takers. Yes, AI bots are now trained to be able to navigate a 48-question survey with multiple choices, including intelligence designed to eliminate responses that don’t fit our profile.

If that isn’t shocking enough, no two survey responses were alike. Bots responded as if they were in different industries, big and small companies. And presumably by gauging the length and difficulty of the survey, bots seemed to learn to slow their response pace down to more closely mirror the typical speed if taken by human beings, typically completing at similar lengths of time as our population of human participants.

Before we shut things down after discovering what was happening, the bots completed the survey 1600 times out of 2100 starts.

How did we detect them?

The most obvious giveaway was the sheer volume of responses received within a very short time. We had been sending out the survey via email and had anticipated a response rate, based on past experience which was much slower.

Additionally, we could tell by the fake emails they created. The bot submissions ended with false gmail accounts (an email was required in order to receive the gift card award – easily spotted as garbage.

How to prevent this in the future?

According to our head of research, Steve Wolf, recommends five things to consider in order to prevent bots from hijacking your survey:

- Gauge expected response metrics – starting with a trusted, proprietary sample of responders (e.g., a client’s customer base) can provide a baseline of start and completion rates, and time per survey, when taken from living breathing humans.

- Create a unique link – don’t rely on one master weblink to the survey, which would make it very difficult to identify which respondent is coming from where. Instead, assign a unique URL per channel (such as email, client website, social media). This way, one can isolate bot submissions to the channel which they took over.

- Add open ended questions – bots have gotten smarter, but they still are unable to answer open ended questions…yet. Sprinkle in 2 or 3 open ended questions throughout the survey.

Use a “trap question” – trap questions ask the survey taker to take an action proving they’re a human – similar to a CAPTCHA. For example, a survey asks “please enter the number 32”. Bots are best at reading multiple choice surveys and picking an option.

- Try adding an invisible question – using a hidden question is another way to trick a bot. Use white font on a white background. Since humans can’t see the question it will always be skipped, but bots will answer it.

And unfortunately, the best option would be to avoid tempting bots in the first place – especially as AI bots become more and more sophisticated. Just avoid “open” surveys – such as those promoted on social media channels or advertised via banner ads – and recruit target participants from other “closed” sources such as email, or at least “quasi-closed” sources such as company newsletters or blog posts.

Lastly, today’s researchers must be especially diligent on reviewing the completed surveys. If you are using a financial incentive to drive survey completions, know that there are bad actors out there looking to cash in.

More Bot Bad News

More and more people are using AI assistants to read and respond to emails. As a result, it is impacting your campaign success rates.

We just switched email platforms. Our company newsletter was the first item to be sent and the performance dropped significantly. Open and click thru rates were half of what they historically had been. The reason? The new platform can filter out bot/agent responses.

For the most part, marketers have been focused on the upside of AI, in particular, generative. What has been missed for the most part is the impact of AI on our results. As I just illustrated, AI bots are disrupting our marketing research efforts, and AI assistants are distorting email response rates. Expect more disruption as AI agents become better at understanding workflows.

AI is turning out to be a double-edged sword. The focus of last year was mostly application and production. This year, we will need to make the time to start considering the impact it will have on our efforts. Or, maybe just program your own bot to figure it out.

by Christina | Feb 13, 2025 | 2025, Business Trends

Sales may be a “numbers” game but selling is not.

We often confuse the two. Treating prospects as a “number” that we need to reach more broadly, and more frequently.

I had the opportunity this year to evaluate a half a dozen new AI enable sale and marketing tools on the market. New tools that promise the world but at the end of the day they deliver basically the same thing we are using tools for today.

- Volume – aka scale, scratching the “reach more’ prospect itch

- Speed – scratching the “more frequently’ itch

- Efficiency – an output of speed and some interesting capabilities to improve productivity

If the goal is greater efficiency you’re in luck, but if it’s efficiency AND effectiveness you’ll be disappointed.

Why? Because performance is not a scale or speed issue, in fact, they make it worse. To get to the root of the performance problem, you have to do post modem on stalled or lost deals.

Here’s what we’ve seen based on our assessments:

- Corporate Priorities – as in you’re no longer on it, priorities shift all the time as well as budgets, this one is interesting because companies often come back to solving the issue at some point

- ROE – the costs, the solution, resources investment, timeline, roi, etc. and/or some combination of those kills the decision

- Motivation – loss of sponsorship, other priorities, effort level, elements of ROE slow the progress

- Inside Job – they did it themselves, gave it to an existing vendor, picked someone they knew/trusted, etc.

Can you think of any sales or marketing tool that can fix the bullets above? If you answered no, you’re right, because they are “selling problems.”

Keep that in mind as you’re watching demos of the latest and greatest.

by Christina | Jan 23, 2025 | 2025, Tech Trends

As previously published on 1/16/25 in MarTech

An interesting piece of research was released last week but may have been lost in the busy holiday season.

Previsible, an SEO consultancy, announced that traditional Google search has “basically plateaued and has begun to have its search dominance degraded.” Why? People are using AI assisted search because it has gotten more capable and accessible.

ChatGPT, Claude, Co-pilot, and even Google, offer an AI search version available to most users. Compared to the traditional search, which relies mostly on keyword matching, AI search uses advanced algorithms to understand the context and intent behind the query. As a result, at least in theory, it should provide more relevant and personalized results.

The new capabilities and changing user behaviors are creating a potential warning about the risk of relying on AI. Because of AI’s ability to draw upon vast amounts of information, users often default to trusting that the query output is most likely to be the right answer, solution, recommendation, etc.

As opposed to the traditional search which returns the links to what are the most likely options to answering the query, the user has to make the effort of analyzing the results, reading and filtering information, and drawing conclusions.

And here lies the potential problem.

Nvidia’s CEO, Jensen Huang, stated on the company’s most recent earnings call that we are “in the beginning of a new generation of foundation models that are able to do reasoning and long term thinking.”

Cognitive scientist Gary Marcus says the AI we are currently building is basically like “System 1 thinking,” a reference to Noble Prize winning psychologist, Daniel Kahneman’s, “Thinking Fast and Slow” book.

In his book, Kahneman explains the dichotomy of human thought. System 1 being intuitive and fast with no voluntary control. This being one of the reasons he concluded that humans are bad at making decisions. System 2 thinking allocates attention to the effort that demands focus, oftentimes because of its complexity and/or need for computations. Think of the two systems as instinct or “gut feel” and critical thinking.

If, as the AI experts state, we are building System 1 AI models then users are at risk of making the same mistakes using AI as they might make in day-to-day decision making. And, as an observer of younger generations of marketers using AI, they may be particularly vulnerable.

My son, home for the holidays from grad school, mentioned that classmates are not only using ChatGPT to summarize course work, but also to write their presentations. And…they’re not questioning it, they follow the recommendation completely because it “saves time.”

B2B marketers are using AI tools profusely for research, writing, and recommending actions because they are “quick and accurate.” They have grown up in an environment that has emphasized scale and speed, and they lack the experience or interest to question the accuracy of what is being outputted by AI tools.

Where is this headed? Combine all of these factors and it could point to a massive wave of “group thinking” marketers that either lose the ability to think creatively and/or strategically, or eliminate it completely because they are wired to trust AI.

Generative AI has already come for the creative department as witnessed by Omnicom’s recent acquisition of IPG. If marketing executives don’t act now to create a plan to manage AI, “Hal” could become your CMO in a few years.

How should marketing executives respond to this threat? Daniel Kahneman might suggest focusing on skill development that emphasizes System 2 thinking. Teach your team how to do long term, critical and strategic thinking.

Combine the strength of using AI System 1 thinking to enable your staff with training on higher level System 2 type efforts like competitive intelligence (which I rarely see any more), market intelligence and strategy.

There is good reason to get back to these core strategic marketing building blocks. Marketing performance in 2024 was significantly down across channels and activities. It’s time to dig in on strategy. There are significant challenges to address. Going faster and creating more noise in the market is not a strategy that will win.

In 2017, I wrote an article on how Amazon had become the default search engine for buyers who knew what they wanted based on our research on buying behavior. In that post, I predicted that because of that trend, Amazon would soon eat away at Google’s advertising monopoly. At that time, Amazon only had 1% of the global advertising market. By 2020, it had grown to over 10%. This year it will be 14%, and by 2026, it’s estimated to become over 17%.

I see a similar trend with AI eating away at the marketing department, not because of the tools themselves, but by how behaviors are changing because of them (similar to what I observed with consumers and Amazon). To be clear, it’s not necessarily the technology that is the threat, but rather the behavior change caused by it.

If marketers want to remain valuable inside their organizations they will have to learn how to use AI tools to enable better decision making and not default to them as the decision maker. Or as my son’s professor said; “use them to become a better student, not to be the student” and remember, they’re only System 1 thinkers 😉.

by Christina | Jan 10, 2025 | 2025

As previously published on 11/27/24 in MarTech

Artificial Intelligence search company, Perplexity, has raised three rounds of funding this past year. They have now begun their fourth round of funding which will value them at more than $8 billion.

The startup seeks to challenge Google’s supremacy in search by combining the best of traditional search functionality with providing answers to questions similar to ChatCGT. The company currently has annualized revenue of slightly over $10 million. It recently launched an enterprise version for corporate customers that will search internal files.

Last year, we signed an agreement with an AI startup who provided that same enterprise functionality. This year, we didn’t renew the agreement because it’s now built into our Google Workspace platform, Gemini. We went from paying $150 per month, to $10 per month, for the same functionality. See what Google did there?

Guess who else is playing this same game? Hmmm…Have you heard of Copilot, Microsoft’s new “AI Companion.” The partnership and investment with Open AI has all the bells and whistles as Chat GPT 4.0 (see below).

There is a free version, a Pro version (priced similar to Google Gemini for $30 a month), that will integrate into your Microsoft 365 suite.

With a voice interactive interface ( four voice options), you can now delete your Amazon Alexa, Calm, Apple News, and many other apps, if you choose. See what Microsoft is doing?

Apple has quietly acquired more AI companies over the last three years than any other company in the world. Last year, they acquired 32 companies in the AI and machine learning space, almost twice as many as Microsoft. The new IPhone 16 with Apple intelligence is just the beginning.

Oh, and let’s not forget Facebook, who is in the process of launching new tools via Meta’s Ads Manager now, and throughout next year. Ad creatives will get new background, image and text generators.

All of this is happening at a time when marketers are looking to consolidate and/or reduce costs related to their martech stack. According to MarTech’s latest Replace Research, 61% of respondents said the number one factor for a replacement solution was cost savings.

Every technology wave brings about winners and losers, but it also creates an evolution, a better way to accomplish something. The dot com bust gave us Amazon, Ebay, Coupon.com and new ways to buy traditional products more efficiently. AirBnB, Uber, and Venmo emerged from the ashes of the “Great Recession” of 2008, providing us with more efficient ways to buy and pay for services.

The AI bubble will produce a similar set of winners and losers. It has already provided us with new ways to create code, images and content. But, outside of Open AI and Antrophic, it’s not clear who else in the AI generative space will be a winner.

One thing is sure. We are only at the beginning of the wave of AI solutions. According to CB Insights, AI startups are currently getting one third of all investment dollars with B2B startups getting $10 to every $1 invested in B2C applications. As a result, we know we are going to see more and more AI applications aimed at B2B marketers.

For Perplexity, will it emerge as an AI winner or will Google put it out of business by building its unique functionality into search? Marketers are facing a similar question, which may come down to opportunity cost. Is it worth the expense and time of learning a new tool, or do we play the waiting game to see if our current platforms integrate the functionality?

Perhaps I am drawing the circle too small by just focusing on integration and costs. Carrie Mahon, CMO at Unanet point of view is “Embracing new AI tools early not only provides marketers with a strategic advantage in creativity and efficiency but also fosters a mindset shift that speeds up AI integration and unlocks greater benefits. Delaying could mean missing out on these initial advantages and innovation opportunities in a rapidly evolving tech landscape.”

Could the real value and strategy be experimenting with new AI technologies, although perhaps costly, and then moving to more efficient platforms as they become available. Capture the opportunity to learn and experiment, then become efficient.

As an old IBM client once said about new technologies “Let a thousand flowers bloom then cut them all down except for the tallest few.” He would then follow up with “make sure that you tend to your garden!”

Maybe the AI wave is not a bubble to burst, but rather a garden to nurture.