by scott.gillum | Jul 1, 2014 | 2014, Marketing

I just spent a week in the Caribbean on an island with lovely beaches and an incredibly high cost of living. The island has no income tax, so generates the majority of its income from tourist like you, and I, through a very large VAT tax.

Simple staples, like bread, are priced so high it made me ask my wife “How does anyone afford to live here?” The answer became apparent as the week went on — you’re either very wealthy (not us), or that you live very simply.

As the week progressed, I found myself appreciating the fact that less could be more. Once my awareness was raised, I discovered a certain elegance in the simplicity. For example, the cabinets and crown molding in our room were white washed rather than covered with layers of expensive paint, actually highlighted the natural beauty of the wood grains.

Arriving home to the states and the “routine” with my newfound appreciation for minimalist living, I found that I am now highly sensitized to the waste within marketing. The unnecessary use of “empty” words used to make extravagant and/or over inflated claims that is cluttering copy.

Arriving home to the states and the “routine” with my newfound appreciation for minimalist living, I found that I am now highly sensitized to the waste within marketing. The unnecessary use of “empty” words used to make extravagant and/or over inflated claims that is cluttering copy.

It appears that with the proliferation of content marketing we are starting to see an ugly underside. Marketers focused on getting “views” and social shares, are in a “war of words” that is producing empty promises in the form of audience grabbing headlines that fail to pay off with insightful or promised content.

Words like “epic” or “iconic” once rarely used, (and when they were, they were actually describing something that was of a significant historical event) are now used to describe everything from trade shows to webcasts, so overused, they have become meaningless.

In the past, when someone made the statement that they were the “Leader in”, they actually were, and could back it up. Or when they created a “Top 5 List or Best Practices”…they had the research to actually prove it. Now marketers randomly use those enticing titles in headlines in a desperate attempt to get noticed.

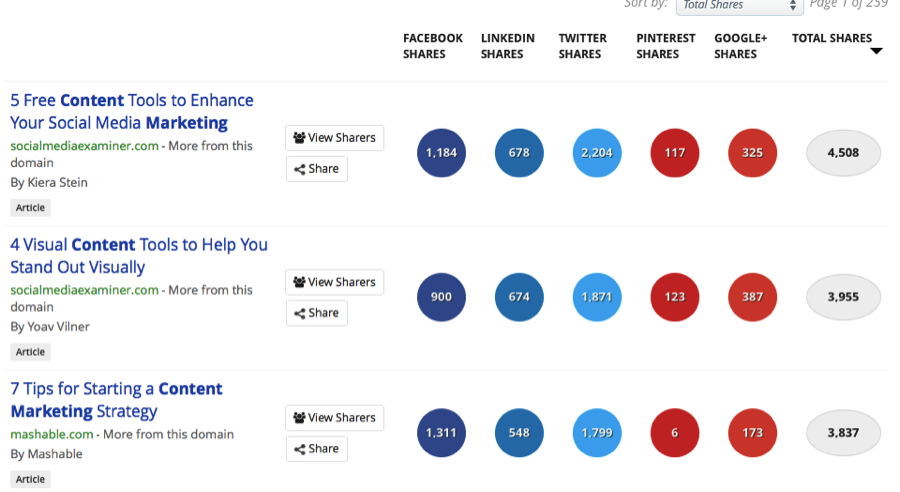

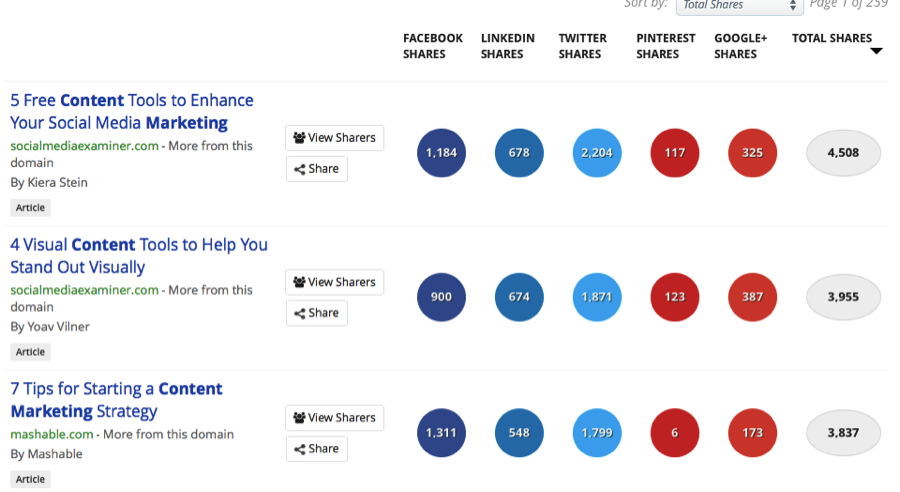

Fueling this are insights from content marketing tools are enabling marketers to engage in this “copy cat” hype game. Just pick a topic, go to a site like BuzzSomo, search for the most popular headlines, and then build something similar.

Content marketing, and for that matter Native Advertising, can benefit audiences and be effective marketing tools, but not if these practices continue.

Thanks to Steve Jobs and Apple, simplicity and “clean lines” are now pervasive within design. It has helped to streamline and simplify brands, from logos and website to products. The time has come for it to influence copywriting and content production.

Yes, it takes longer to write a shorter sentence, but it’s worth it. As the late great Maya Angelou once said, “Easy reading is damn hard writing. But if it’s right, it’s easy. It’s the other way round too. If it’s slovenly written then it’s hard to read.” As marketers, we have to do better, be better. Strive for elegance in your craft. Don’t paint the essence of what you want to say, or promote, with layers of needless or empty words.

If you want someone to read your content — be credible. If you want it shared, say something insightful or newsworthy. That is the way it has been, and will always be. It’s that simple.

by scott.gillum | Jan 13, 2014 | 2014, Opinion

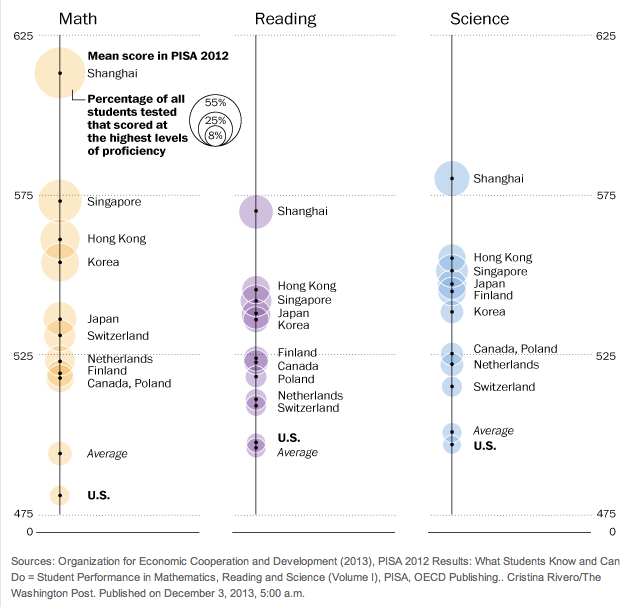

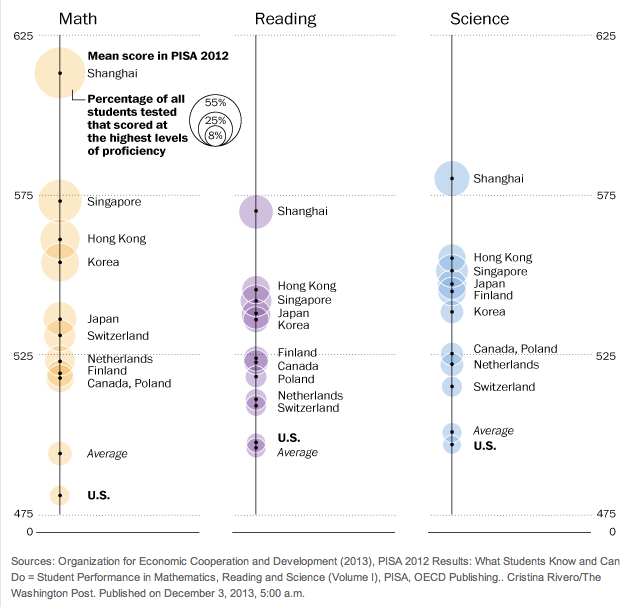

At this time of year the test scores of high school students from around the world are released. US student performance on the PISA Math, Reading and Science tests are compared to their peers from 55 countries. And every year we hear how our kids scored at the “average” level, seemingly falling further behind a half dozen or more countries.

But are these results really indicative of our future success, are we really doomed to losing our “competitive edge” as some critics would argue?

But are these results really indicative of our future success, are we really doomed to losing our “competitive edge” as some critics would argue?

Maybe not, according to Peter Sims, in his book Little Bets. Sims argues that educational systems are built upon teaching facts then testing us in order to measure how much we have retained. Students who are taught to solve math problems, for example, focus on learning established methods of logical inference or deduction, both highly procedural. Improving test performance is a matter of becoming more proficient at retaining and applying established practices.

The risk, according to Sims, is that students are graded primarily on getting the answers right, and not encouraged to creatively problem solve using their own methods. The consequence is that our right-brain capacities to create and discover get suffocated.

This overemphasis on left-brain analytical skill development is a concern for many educator reformers. As author, Sir Ken Robinson, describes it in his Ted Talks video Do Schools Kill Creativity? “We are educating people out of their creativity.”

Robinson argues that the modern education system was crafted after the industrial revolution to support operational management practices that emphasize efficiencies and productivity objectives. But the emphasis on sequential processes, regimented systems and detailed planning results in the stifling of innovative capacities.

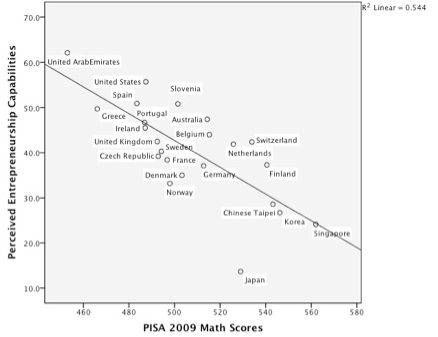

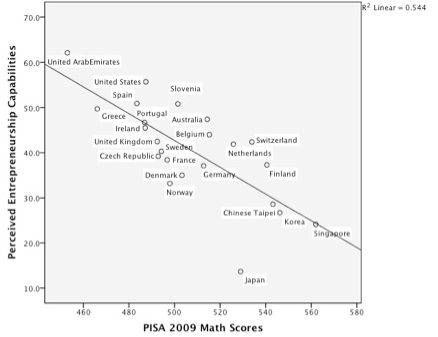

In doing research for his new book World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students Yong Zhao compared the results of the PISA Math scores and the GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor) annual assessment. GEM assesses the entrepreneurial activities, aspirations and attitudes of individuals in over 50 countries, 23 of which participate in the PISA test.

Zhao found an interesting and surprising result. There was an inverse correlation between test scores and perceived entrepreneurship capabilities. Top PISA performing countries like Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Japan, scored the lowest on perceived capabilities or confidence in their ability to start a new business.

Zhao found an interesting and surprising result. There was an inverse correlation between test scores and perceived entrepreneurship capabilities. Top PISA performing countries like Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Japan, scored the lowest on perceived capabilities or confidence in their ability to start a new business.

This also highlights another important, and often overlooked result from the PISA findings about the importance of the mind-set of the students taking the test. As the article in the Washington Post noted;” Despite their tepid math scores, U.S. teenagers were more confident about their math skills than their international counterparts…”

Research from Dr. Carol Dweck, a professor of social psychology at Stanford University, a leading expert on why people are willing (and able) to learn from setbacks, found that people tend to lean toward one of two general ways of thinking about learning and failure; fixed mind-set and growth mind-set.

Fixed mind-set students believe in their abilities and innate set of talents, which creates an urgency to repeatedly prove those abilities, and perceive failure as threatening to their sense of self worth or identity. They are likely to be overly concerned seeking validation, such as grades, test scores and titles.

Fixed mind-set students believe in their abilities and innate set of talents, which creates an urgency to repeatedly prove those abilities, and perceive failure as threatening to their sense of self worth or identity. They are likely to be overly concerned seeking validation, such as grades, test scores and titles.

Students identified to be growth-minded believe that intelligence and abilities can be developed through effort, and tend to view failure as an opportunity for growth. They have a desire to be constantly challenged.

In her research with elementary school students, Dweck found that mind-set is strongly influenced by what a student thinks is more important: ability or effort. She found that students praised for their effort, “You worked really hard” versus ability “You must be smart”, where more likely to chose the more difficult task and creatively problem solve. Most importantly, when they failed they did not think their performance reflected their intelligence.

This insight would help to explain why students who are seen as “failures,” in the tradition sense, like Steve Jobs, are able to succeed and thrive in the face of diversity. It also helps to explain why in the US, students like Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg, who drop out of college, which would be shameful or unheard of in other countries, are able to go on to build billion dollar companies and change the world.

As the parent of two high school children, I’m not saying that testing student abilities doesn’t have its merits, but I am suggesting it isn’t the only measure of predicting a student’s, or country’s, future success.

The US has had a long tradition (and a culture) of producing rule breakers, game changers and out of the box thinkers. All of which is not easily measured by test scores, but better captured in the form of optimism, perseverance, and innovation. Perhaps being “average” is the right result to ensure that we are not, as Robinson would say, “educating people out of their creativity.”

Arriving home to the states and the “routine” with my newfound appreciation for minimalist living, I found that I am now highly sensitized to the waste within marketing. The unnecessary use of “empty” words used to make extravagant and/or over inflated claims that is cluttering copy.

Arriving home to the states and the “routine” with my newfound appreciation for minimalist living, I found that I am now highly sensitized to the waste within marketing. The unnecessary use of “empty” words used to make extravagant and/or over inflated claims that is cluttering copy.